A quick note for those of you are also subscribed to my Acknowledge Substack—I’m publishing two very different essays about Emma Austin today. I enjoyed some of the creative conventions I employed in my last piece about an ancestor so much that I decided to lean more into that style of writing with this version of her story. Hope you enjoy!

“You’re late,” Emma chides. “The tea turned cold, child.”

“I’m sorry great-grandmother. I heard you years ago when Vineyard City invited me to perform for their Heritage Days festival. Your voice got lost in the choir of all the others. After hearing that I wanted to tell about the history of the lake’s original peoples, the Timpanogos, Mayor Fullmer retracted the invitation and I moved away from developing the piece.”

“All is well, dear. I warmed it up again. No trouble. You’re here now.”

Here appears to be a small tea room in a 19th century hotel in Central Utah. I notice the dense, dark brown slices of bread buttered and thoughtfully placed on a piece of china. I wonder if there’s any molasses in them. God, when was the last time I thought about molasses? I wonder.

The window behind us is open. A cool breeze blows in from the blue lake. The air is as fresh as the ironed white tablecloth beneath the tea set. “Why did you call me here, grandmother?” I ask.

“To have a spot of tea. Cream, sugar?” I’ve hosted enough tea parties for the dead now, I figure there might be some symmetry in this happening in the reverse. I like being here, in Emma Austin’s hotel. It’s quiet, cozy.

For a second my mind flashes to that hidden room beneath the staircase, where she would hide polygynists when government officials came looking for them. My toes squirm beneath the table in response to the goo I feel slogging through my insides when I think about that situation. “Did you catch what that Vineyard historical society leader said?” Emma looks up from the tea she is pouring, a wry look on her face. “Are you referring to the man who asked about the farmers, dear?”

Irreverence leaps out of me before I can restrain myself. “I told this historian that I wanted to perform about the genocide of the Timpanogos—the native peoples of that lake,” I gesture out the window. “The lake upon which Vineyard would eventually be built, and he told me that their historical society had hoped for a story about the farmers. Can you believe that? ‘What about the farmers?’ I wanted to say.”

Quiet grows between us. “That’s when I thought of you,” I prattle on. “I wondered how you would tell this story.”

“You are aware that my sons were farmers,” Emma says.

Her clipped tone surprises me, but she’s right. I do know a lot about this family. Among my Mormon ancestors, the Austins were the last to convert to the faith. They traveled across the West not by handcart or wagon, but by train.

Their journey began in Bedfordshire, England. A ship called the Minnesota carried them across the sea to America. That was in 1868, one year after the Timpanogos who survived the genocide were relocated from the shores of Utah Lake to Heber, Utah, which at that time was recognized as a part of their reservation.

My mother’s family have been Mormon almost as long as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been in existence. With the exception of a few Scots, her Mormon ancestors were uniformly English immigrants, or they descended from Revolutionary War era American families. I believe this must be why they named it American Fork.

My third great-grandfather, Stephen Chipman, who descended from Mayflower passengers in such a uniquely fabulous way that my family still won’t stop talking about it, is known as the founder of American Fork. Another progenitor, Joseph Stacey Murdock, was the first bishop in Heber. Once they got to Utah my mother’s family homesteaded in a forty mile radius for about 100 years. It just so happens that this radius coincides with the Timpanogos’ original ancestral territory.

From what I’ve gathered over my years of research, Mormon immigrants liked to build communities with others from their homelands. There was an enclave of Swiss people who ended up in Midway, Utah. Lots of Swedes up in Box Elder County. A group of Danish immigrants settled San Juan County. But the Austins, they were English.

“Yeah, I read about how your sons worked in the sugar beet fields, and eventually manned the beet factory that was built on the lake,” I say. “And then, at some point, they amassed enough money to buy Saratoga Springs, which included acres of lake front property. I read that your children and grandchildren would have reunions cruising on the lake. Truth is, I can’t tap into any joy when I read that. I only feel sad.”

It is a tremendous oddity to me that on the paternal side of my mother’s family I would have ancestors who carried out the genocide, and on the maternal side of my mother’s family I would have ancestors who were among the first to industrialize and commercialize Pagadi’t, the lake. What a strangeness that I would snap to one day and see so many of the threads of my life appearing in one extremely misused body of water.

The only time I’ve ever been in the lake it just so happened to be Pioneer Day. It was really warm on Pioneer Day 2013. Hot enough to make Utah Lake appealing. I slipped on jagged rocks while wading in, and I banged myself up so badly that I had to miss a wedding the next day.

But, back when Emma Grace was hosting and cooking for her hotel guests, the water wasn’t turbid and polluted, not like that. That was before the carp infestation. Back when it was still teeming with native fish species.

I finally pipe up. “Grandmother, I don’t know what to say about the farmers,” I offer. “Was the situation in Bedfordshire truly so oppressive that you felt like you had to come all this way to Utah and take this land from the Timpanogos?”

“We didn’t have anything to do with that,” Emma replies. “By the time we arrived they were already run off the land. A few would come back to fish in the summers occasionally, but we hardly ever saw them.”

“Run off the land is a nice way to describe what happened.” I let that sentence hang in the air for a moment. “Did you know?” I ask her. “Surely some people didn’t know.”

Emma steels herself, and takes a deep drink of her tea, her face pinched as though she’s swallowing a tonic. “We knew,” comes the reply. “Everyone at home in England had heard the wild tales of the cowboys and the Indians. It was common knowledge that they lived here before we did. We had to do whatever God asked of us to build our Zion. Lamanites, as I’m sure you’ve heard tell. The cursed ones…”

She trails off. The faraway look in her eyes reveals her true feelings on the matter, however subtly. “We thought ourselves lucky to have arrived after all of the carnage. Of course, the missionaries didn’t tell us the full extent of what had happened. Who knows if they knew. We heard some of the details after we arrived. We could pretend it didn’t happen. And so we did.”

Emma picks up a small spoon, swirls in through her tea cup, and then politely taps it on the rim of her cup. That faraway look in her eye comes back, and she softly sings a folk melody I’ve heard somewhere before.

For when your thyme is past and gone

He'll care no more for you

And in the place your thyme was waste

Will all spread o'er with rue

Will all spread o'er with rue

In the weight of her admission I nurse the warm tea she has poured for me between my hands. When I bring it to my lips the taste is so rancid that I spit it out. “Grandmother, what is wrong with this tea?” I query, bewildered.

“I asked if you wanted creme or sugar, dear.” I reach for the sugar, but recoil when I open the lid. Sugar cubes are covered in black mold. I look inside the porcelain pitcher. The creme is curdled. “What is in this tea, Grandmother?” I ask.

“I draw water from the lake to steep this tea. It pairs nicely with lemon, when we can get lemon.”

“Don’t drink that!” I bat the tea cup out of her hand onto the floor. She looks at the broken, wet pieces of china strewn against the floor unphased. Gracefully, she stands, walks to the cupboard, and pulls out another cup and saucer. She sits again, pours herself more tea, and carries on as if nothing has happened. “This tea is all I can drink, dear. It’s what I serve here in my tea room. If you’ve come to visit me, this is what I have made, and this is what I can offer.”

I study my cup. I can see the algal blooms I mistook for herbs swirling in the liquid now. Is this a trick? Yet another poison I should be avoiding? Whose grief am I imbibing here—hers, mine, the lake’s? I give it some thought, and conclude that I cannot come up with a good reason to drink this tea. Emma takes another sip, and I watch her wince again.

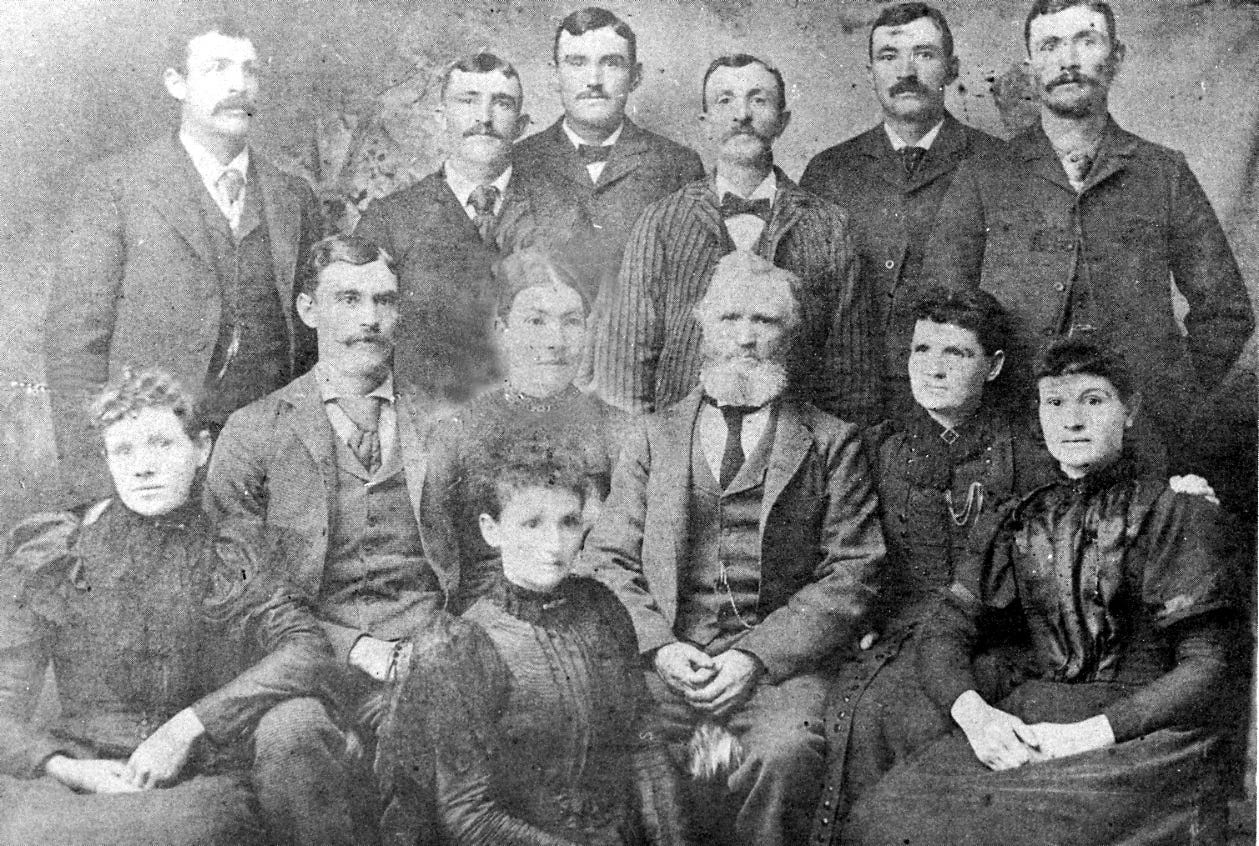

I reach across the table and knock it out of her hands a second time. Her eyelids flicker in perturbation. She stands calmly again, returns to the cupboard, fetches a new tea cup and pours herself more of the toxic brew. “I birthed 17 children, dear. You’ll have to do more than break a few teacups to get under my skin.”

Let’s test that theory, I think to myself. This time I stand. I push in my chair, and drop my napkin on the table. I walk right up to her, snatch the tea cup out of her hand and smash it on the floor with all the gusto of a Norse viking breaking an ale vessel after a battle. I hold her gaze throughout the whole exchange, challenging her to break.

Nothing. All composure, all control, she stands up, meets my gaze, and before you know it, we’re back at the table each of us holding one tea cup as before. Things are heating up. The straw bonnet constricting my throat, and the scratchy fabric cinching my wrists tells me this is so.

“Did you know, dear, in England I was a milliner. I taught my daughter to make those straw hats, and one summer we got word that Brigham Young himself had heard about how fine the craftsmanship was. He was coming to Lehi for a parade down main street, so my daughter and I bedecked all the sisters in our ward in our hats, and Brigham put in the biggest order we’d ever seen. Soon enough all the fine ladies in Salt Lake City were wearing them.”

I reach up and tug at the ribbons that have tied themselves under my chin. They seem to be getting tighter. The corset under my dress is tightening too. My great, great, great grandmother, Emma Grace Austin, looks at me, and slowly raises one eyebrow. “Your tea is getting cold, dear. Where I come from, where your ancestors come from, it is considered very rude not to receive what has been prepared for you.”

Oh hell no. I didn’t sign up for this. I am not drinking this tea.

“Fuck Brigham Young, Emma. Fuck him straight to hell,” I say. Emma’s eyes go wide for a moment. Her mouth drops open a quarter of an inch. Her hand trembles and her cup tinkles against the saucer. The easiest way to crack a Mormon woman is to scandalize her, but the window only opens for so long. So, I drive the wedge in a little deeper.

“Don’t try that fragility shit on me. Your husband isn’t here to step in and tell me to back off. Nobody’s coming into this room to try and make me responsible for the way you fear your own power. It’s just you and me, baby girl. What are you gonna do about it?”

Confusion flashes through Emma’s eyes. She sputters, “In all my years, I have never…”

“Never what? Never been visited by anyone? Yeah, that’s what I thought. You’ve been sitting here, a ghost trapped in time for 150 years and nobody has come to visit you since you died. You know why? Because they’ve all been drinking this goddamn tea of yours. They’re all asleep—every single one. I’m the lucky daughter cursed with sight, and so I came back here for you. The first time you contacted me you told me you wanted to grieve over Utah Lake, and you wanted to be seen while doing it. I’m here. Where are your tears?”

Emma rises, “You cannot speak to me this way,” she insists.

“I’ll speak to you however I want.” I rip her bonnet off my head and throw it on the ground. Then I go for the prize. The teapot she carried with her all the way from England. “Was this your mother’s?” I ask. “You can replace teacups and saucers, but this is an heirloom, isn’t it? You can’t replace this.” I grab the teacup, and I sprint out of the hotel, making like a bandit for the lake.

Emma gives chase. “No!” she shouts. “It’s all I have left!”

“All you have left of what? A fantasy? Your mother neglected you! Is that why you keep drinking poison?”

I run like my life depends on it, because, frankly, it does. The tall grasses graze my hands as I sprint for water’s edge. I call to the earth for help and clouds gather. Rain begins to pelt my face. Her demons fully unveiled now, Grandma Emma furiously chases me.

“How dare you come into my home and degrade me? How dare you take my mother’s teapot? You are no kin of mine.”

In the past this would have stung, but now it’s just fuel. Somehow, I manage to find enough breath to shout back, “No, baby girl. You don’t know it—but I’m the best kin you’ve ever had. I’m the one who loves you enough to ask you to stop drinking this poison.” I’m drunk on the potency of my own love. My throat rolls with laughter, but my feet are increasingly steady beneath me.

I arrive at water’s edge. Rain streams down the jagged rocks. The wind howls through the reeds. Thunder gathers in the sky. I manage to slip and slide up the tallest rock before Emma catches up to me.

Her bun has been pulled loose. Her face is drenched, and her skirts are heavy with mud. She can’t reach me here. All she can do is tantrum. Water gushes down the rocks and she cannot climb to where I stand, no matter how much effort she exerts. She screams and I can barely hear her over the thunder.

“I have been steeping that tea for a seven generations! It’s all I have left!” She falls to her knees. “Let me have it! Let me atone for what I’ve done! Please, I can’t live without that teapot.”

I look at her, more bewildered than I have ever been. I shout over the thunder. “You mean to tell me that you are feeding yourself poison because you think that’s how you must atone for what your sons did to this lake? Is that what your mother taught you love was?”

Emma is on her hands and knees, sobbing now. “I’m so sorry!” roars out of her. It’s the guttural cry of a laboring woman. Grief lashes through her body like the sheets of rain falling through the sky. It’s the most cathartic thing I’ve ever seen. “Emma, look at me. Look at me.” In the throes of her agony her eyes find mine. “We have to let this go.”

I set the teapot down. I place my hands on the collar of this inherited pioneer dress I find myself wearing, and with a mighty cry I shred it in two. It falls to the ground, on either side of the rock I stand upon. I rip off the girdle and the garments. I untangle myself from the corset and throw it to the ground.

Thunder quakes through the atmosphere and I bellow with it. “You can do what you like, Emma, but I refuse to be held captive by this any more. I will be free.” I hold the heirloom above my head, and I bring it down on the rocks with a mighty crash.

In my power now, as much as I’ve ever been, I dive into the lake behind me naked as the day I was born. I swim out into the water, and roll over onto my back. Ever faithful love is there, holding me again, as it always does. I hear a splash.

Emma! She swims towards me, and rolls onto her back. She clutches my hand, and we float side by side, two otters in the lake.

A tepid quiet lingers between us for a time. Then—“Darling, you are incredibly theatrical,” Emma says. Usually when family employs the word theatrical it’s meant to discredit the way I experience the world. “Hearing you say ‘Fuck Brigham Young’ the way you did might be the single greatest thing that has ever happened to me.” She shudders for a moment.

“He truly was a dreadful man, but he’s nothing to fear now,” I say. “His time is over.” Emma searches herself for a moment, and then when she discovers the truth of what I’ve said her body relaxes into the water in delight. Her laugh sounds like a bell. It looks like light streaming from a lighthouse. It’s like nothing I’ve ever heard.

“I read that you were a thespian when you were alive. Shakespeare?” She stands up, nods, dips her head into the water, and stands in front of me. I do the same. She closes her eyes, and a recitation spills out of her.

“Come, let's away to prison:

We two alone will sing like birds i' the cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I'll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness: so we'll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we'll talk with them too,

Who loses and who wins; who's in, who's out;

And take upon's the mystery of things,

As if we were God's spies: and we'll wear out,

In a wall'd prison, packs and sects of great ones,

That ebb and flow by the moon.”

The rain stops pattering against the lake as Emma delivers the monologue. “Oh, I adore King Lear,” I glow. The sun parts and it shines on a woman and her ancestor. “You understand that this is all a dream, and not a dream you’ll live to see fulfilled,” Emma says. “I will carry you as you have carried me. My voice is yours. Sing from the cage, and I’ll sing with you.”

She places her forehead against mine and the antidote hits me between the eyes. Still in the cage I may be, but of this poison at least I am free.